Project

ShutterstockTowards an end to subsidies that promote overfishing

Overfishing is one of the main problems for the health of our ocean. And the provision of negative subsidies to the fishing sector is one of the fundamental causes of overfishing.

Fishing subsidies are financial contributions, direct or indirect, that public entities grant to the industry.

Depending on their impacts, they can be beneficial when they promote the growth of fish stocks through conservation and fishery resource management tools. And they are considered negative or detrimental when they promote overfishing with support for, for example, increasing the catch capacity of a fishing fleet.

It is estimated that every year, governments spend approximately 22 billion dollars in negative subsidies to compensate costs for fuel, fishing gear and vessel improvements, among others.

Recent data show that, as a result of this support, 63% of fish stocks worldwide must be rebuilt and 34% are fished at "biologically unsustainable" levels.

Although negotiations on fisheries subsidies, within the framework of the World Trade Organization, officially began in 2001, it was not until the 2017 WTO Ministerial Conference that countries committed to taking action to reach an agreement.

This finally happened in June 2022, when member countries of the World Trade Organization reached, after more than two decades, a binding agreement to curb some harmful fisheries subsidies. It represents a fundamental step toward achieving the effective management of our fisheries resources, as well as toward ensuring global food security and the livelihoods of coastal communities.

The agreement reached at the 12th WTO Ministerial Conference provides for the creation of a global framework to reduce subsidies for illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing; subsidies for fishing overexploited stocks; and subsidies for vessels fishing on the unregulated high seas. It also includes measures aimed at greater transparency and accountability in the way governments support their fisheries sector.

The countries agreed to continue negotiating rules to curb other harmful subsidies, such as those that promote fishing in other countries' waters, overfishing and the overcapacity of a fleet to catch more fish than is sustainable.

If we want to have abundant and healthy fishery resources, it is time to change the way we have conceived fishing until now. We must focus our efforts on creating models of fishery use that allow for long-term conservation.

Partners:

In search of legal protection for Mexico’s reefs

From the coasts of Baja California to the shallows of the Caribbean, Mexico is home to an incredible array of reefs. The coral and rocky reefs found throughout the country are sources of food and potentially life-saving genetic material. They protect people on the coasts from the impacts of storms and hurricanes, stimulate tourism, and provide shelter for a wide variety of plants and animals. Despite their inherent value, Mexico does not yet have an overarching law for reef protection. This vital task is instead governed by a variety of legislation and by international treaties that establish the country’s obligations to preserve these valuable ecosystems. Climate change is one of the most serious threats to reefs. Oceans are becoming warmer and more acidic, conditions that reduce reefs’ capacity to grow and repair themselves. In addition, warmer water disperses the algae that corals feed on, leaving the corals weakened and at risk of death. This month, the Mexican Senate’s Special Climate Change Commission decided to do something about the threats facing corals. They convened a series of meetings to promote the creation of a legislative instrument aimed exclusively at protecting the nation’s many reefs. I participated in these meetings as a representative of AIDA, alongside our colleagues from Wildcoast and scientists, academics, and community members who benefit from the services reefs provide. We drew the Senate’s attention to the serious threats facing reefs, and to the urgency of applying the precautionary principle to guarantee the human right to a healthy environment, which is at risk due to the lack of adequate regulations for reef conservation. To guarantee this right and to protect the oceans against climate change, Mexico has signed international treaties including the American Convention on Human Rights, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, and the Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles. The Veracruz Reef, an emblematic case Reefs around the country are also being threatened by inadequately planned coastal infrastructure and insufficient environmental impact assessments. This is the case with the expansion of the port of Veracruz, a project that endangers the Veracruz Reef System, the largest coral ecosystem in the Gulf of Mexico. The site was declared a Natural Protected Area in 1992, a priority region for the National Commission for the Knowledge and use of Biodiversity in 2000, a UNESCO biosphere reserve in 2006, and a Ramsar site. Even so, the government reduced the size of that area in 2013 to make way for the port project, violating international conventions such as the Ramsar Convention, under which the Veracruz reef is recognized as a Wetland of International Importance. Learn more about the case in the following video: Hope for Mexico's Marine Heritage We are confident that the Senate initiative will bear fruit and that Mexico will develop a law for the protection of its reefs, and that it will be born from a transparent and participatory process to which we will continue to contribute. To learn more about the topic, see our report The Protection of Coral Reefs in Mexico: Rescuing Marine Biodiversity and its Benefits for Humanity.

Read more

Calling on Chile to protect Patagonia from the risks of the salmon industry

More than half of the salmon farms in Chile’s Magallanes Region are depleting oxygen from sensitive marine waters, suffocating marine life. Civil society organizations filed an administrative complaint and a petition calling on the government to investigate and punish farm operators, and to enforce existing regulations. Santiago, Chile. Civil society organizations filed a complaint today asking the Superintendent of the Environment to investigate damages caused by salmon farms in the Magallanes Region of Southern Patagonia, and to sanction the companies responsible. According to government reports, salmon farms in the area are depleting the water of oxygen, causing a serious threat to marine life. The organizations also launched a citizen’s petition to support the formal complaint. “Salmon farming concessions have been approved in Magallanes without a detailed assessment of the impacts the industry may have on the region,” said Florencia Ortúzar, an attorney with the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense. “The damages are already occurring: a report by the Comptroller General of the Republic found that, between 2013 and 2015, more than half of the salmon farms in Magallanes created anaerobic conditions, gravely threatening marine life.” Chile is the world’s second largest producer of salmon. The industry, which developed on coasts further north, has now entered the Magallanes region in the southermost tip of the country. The pristine waters there are highly vulnerable to human activity. Magallanes has the largest number of protected natural areas in the country; it shelters such protected species as the blue whale, the sperm whale, the Magellanic penguin, the elephant seal, the leatherback sea turtle, the southern dolphin, and the Chilean dolphin. “Salmon farms are cultivating more fish than the ecosystem can withstand. They are filling sensitive waters with chemicals and antibiotics,” said Francisco Campos-Lopez, director of #RealChile. “Those chemicals, combined with the feces of the animals, cause a dangerous lack of oxygen in the waters, endangering sea life.” NOTE: More information available at aida-americas.org/salmonfarms Press contacts: Florencia Ortúzar, AIDA Attorney, +56 9 7335 3135, [email protected]

Read more

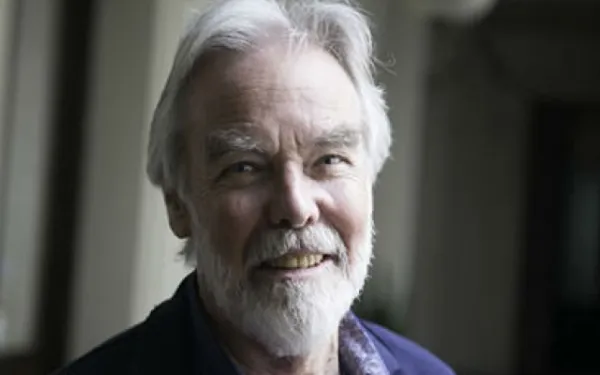

Remembering Robert Moran

It is with great sadness that we share news about the passing of Dr. Robert E. Moran, a distinguished hydrogeologist who was an immense resource in furthering environmental protection globally and a dedicated partner to AIDA. He died May 15 in a car accident while vacationing in Ireland. With over 45 years of experience in water quality monitoring, geochemical, and hydrological work, Dr. Moran was invaluable in the fight for clean water and responsible mining worldwide. His work as an expert on the environmental impacts of mining led him to collaborate with a wide range of actors, from non-governmental organizations and indigenous communities, to private sector and government clients. He was an admirable scientist and a strong defender of environmental rights. Some of Dr. Moran's recent projects in Latin America included: a review of technical issues at the Veladero gold mine in Argentina following a toxic cyanide spill; providing assistance and training to Colombian government officials on coal mine inspection and water quality monitoring; and preparing reports evaluating the environmental impact statements of the Minero Progreso Derivada II project in La Puya, Guatemala. Dr. Moran also conducted reviews of mining operations and their impacts in Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, and Honduras, as well as in Africa, Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, and the United States. He dedicated his life to helping others understand and better evaluate the true costs of mining activities. Dr. Moran will be sorely missed by many in the environmental movement and people everywhere whom his life touched. We honor and thank him for all of his magnificent work to defend our planet.

Read more